by Dot Cannon

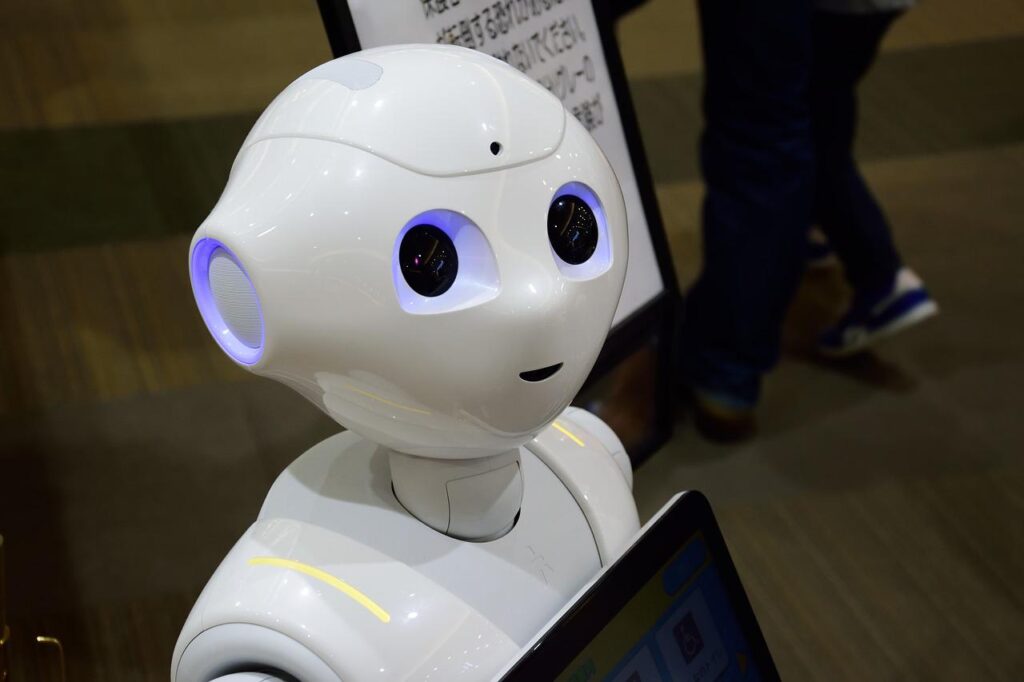

Could you feel empathy for a robot?

According to Dr. Kate Darling of MIT, you absolutely could–very easily.

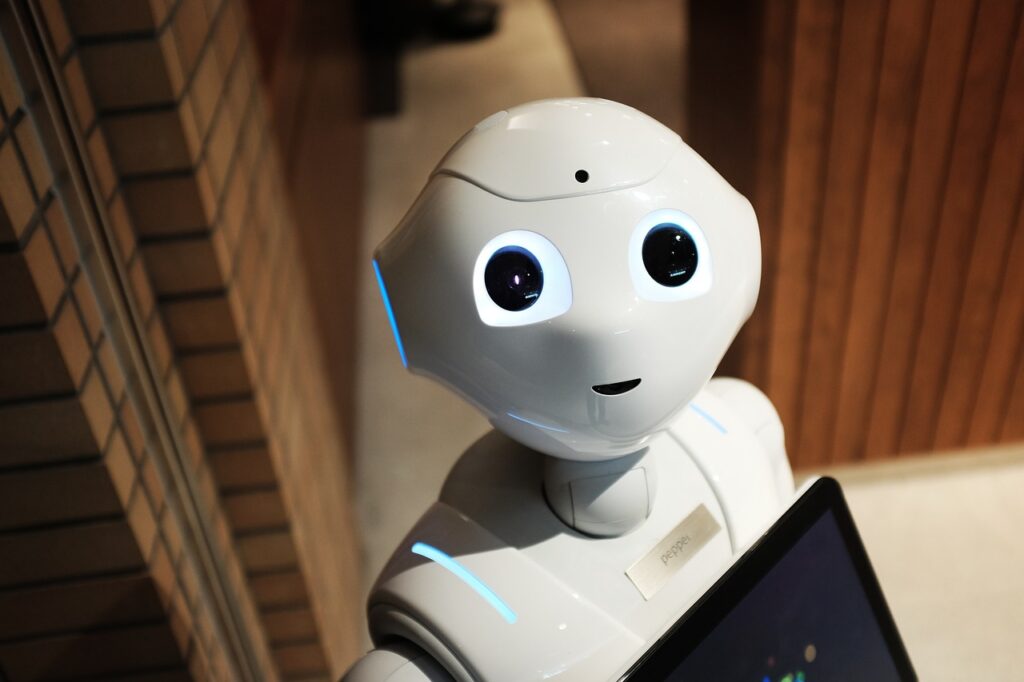

“My interest is…why people treat robots like they’re alive,” Dr. Darling said in her opening keynote presentation. “The Future of Human-Robot Interaction”. on Tuesday morning, as Day Two of Sensors Converge Virtual began.

“Even though they know perfectly well that they’re just machines.”

(As mentioned in our previous post, Sensors Converge Virtual is the only virtual platform for the design engineering community. Besides globally live-streaming presentations, their virtual show content includes exclusive interviews, white papers, and sessions from the 2022 Sensors Converge live event, which took place in San Jose in June.)

Dr. Darling then illustrated our treatment of the machines with her own robot–a toy “Pleo” baby dinosaur.

Introducing it as “Mr. Spaghetti”, she told the audience the robot had multiple touch sensors, microphones and an infrared camera.

“…It can react to a bunch of stuff, and it can mimic lifelike behavior really well.”

Holding the robot up by the tail, she said, “I don’t know if you can hear it. It’s crying.”

And indeed, Mr. Spaghetti was making a sort of grunting sound, mimicking pain and distress.

Research born of empathy

Dr. Darling, who is both a research specialist at MIT’s Media Lab and the author of the book The New Breed, said after buying the toy in 2007, she would have her friends hold the robot up by its tail.

“What happened is, it started to bother me, when they held it up too long. And I would say, ‘OK, that’s enough now. Let’s put him back down.”

She then would pet the robot until it stopped making its “crying” sound!

“That was really interesting to me, because I knew exactly how it worked, but I still felt compelled to comfort it. So that sparked a curiosity.”

Her reaction, she discovered, wasn’t unique.

Several years later, she and a colleague conducted a workshop in Switzerland. They took five of the Pleo baby dinosaur robots with them, giving them to five groups of people.

Then, they had each group name their robot, play and interact with it.

But after a few minutes, Dr. Darling and her colleague produced “a hammer, a hatchet and a knife. And we tried to get them to torture and kill the robots.”

The workshop participants couldn’t do it.

Not even when they were told they could save their own team’s robot by attacking one that belonged to a different team.

Dr. Darling showed a video, where one woman wielded the hammer. She kept looking away from the robot, covering her eyes, and laughing nervously.

Finally, the woman gave up and moved away, without hitting the robot.

Sympathy for the machine

The only way the researchers were able to get anyone to attack one of the robots at all? They threatened to destroy ALL the robots–unless someone took a hatchet to one of them.

One volunteer finally complied.

“As he brought the hatchet down on the robot’s neck, everyone kind of winced and looked away,” Dr. Darling said. “And then there was this half-joking, half-serious moment of silence in the room, for the fallen robot.”

“That (experience) inspired the later research I did at MIT, around empathy towards robots,” Dr. Darling said.

Inside our thinking

So, why do we react with empathy, when we know the robots aren’t real?

“(Humans have an) inherent tendency to anthropomorphize,” Dr. Darling explained.

“…We do it from a very early age. We do it in order to interpret, and to make sense of our world.”

Dr. Darling said that one of the first things an infant learns to recognize, is a face. But it doesn’t have to be a real face.

“It can be a black and white image on a piece of paper.”

Another factor to which our brains respond very strongly, she continued, is movement.

“Studies indicate that we’re constantly scanning our environment, trying to separate things into objects and agents.”

Consequently, Dr. Darling explained, people will tend to treat even very simple robots–like the Roomba vacuum cleaner–like agents, rather than objects.

“The fact that it’s moving around will cause people to name the Roomba,” she said. Over 80% of them have names. ”

And if their Roomba malfunctions, she continued, some people will turn down the offer of a replacement.

Instead, Dr. Darling said, they’ll say, “no, we want you to fix Meryl Sweep and send her back to us.”

In more extreme examples, she said, troops tend to feel a similar connection to their military robots. Bomb disposal units, for example, are given names, medals or even funerals, with gun salutes, if they’re destroyed!

Anthropomorphism in work clothes

So, how can this response to robots be used to advantage?

“It’s actually really helpful to take it seriously, that people treat (robots) differently than other devices,” Dr. Darling said.

“…This is an effect that can be harnessed to pretty powerful effect. This is what social robotics tries to do.”

Social robots, as Dr. Darling defined them, mimic sounds, cues and movements that people automatically associate with states of mind.

Some of the uses of social robots include social skill-building for autistic children, serving as senior-citizen companions and various types of education.

“(People aren’t afraid to make mistakes because a robot doesn’t judge them),” Dr. Darling explained.

AI: an important distinction

However, she said, when people think of AI, there’s a misconception.

“Artificial intelligence is not like human intelligence,” Dr. Darling said.

Machines are “smarter” than humans at math and recognizing patterns and data, she explained. But what humans can distinguish, machines can’t .

“Automated vehicles will slam on the brakes if there’s a truck in front of them them that has an advertisement with a human figure, because they think it’s a pedestrian.

“Or, this AI cannot recognize that this (slide) is a cat because the paws are hidden. And my one-year-old will immediately recognize this as a cat. And it’s not because the AI isn’t smart. It’s because the AI has a different way of identifying things than my child does.

“Most importantly, the question to me is not ‘can we re-create human intelligence?” Dr. Darling continued.

“Why would we even want to do that in the first place, when we can create something that’s different?…It shouldn’t be our goal to create something we already have. That’s boring.”

A new perspective on robots

Rather than seeing robots as much-smarter ultimate replacements for humans, Dr. Darling suggested a “thought exercise” in which we consider them as having new possibilities in different areas.

The example she cited was the PARO: a baby seal-like robot used as a companion to patients in nursing homes. But the PARO, she said, isn’t meant to replace human care.

“That would be terrible, if that was what we were doing. But this robot has been designed…to replace animal therapy. In contexts where we can’t use real animals, for reasons of safety or hygiene.

“That’s pretty cool and it’s a pretty interesting new tool, when it’s designed and used for the right purpose…as part of a more holistic model of care.”

Addressing a common myth

This new model, Dr. Darling continued, contradicts the decades-old rhetoric of “no jobs, blame the robots”.

“Really, we do have some choices,” she commented. “We could be investing in technology that helps people do a better job, rather than trying to automate them away.

“…There are some companies that are starting to use the concept of extended intelligence, or augmented intelligence,” Dr. Darling said.

An example of a company that could benefit from this intelligence, she added, is the U.S. Patent Office–which has to sift through “all the world’s information” to determine whether an idea is new–and can therefore be patented.

“It’s not, ‘how can we automate away these pesky workers’, it is ‘how can we do a better job.’ “How can we use technology to help people be more productive?”

“That is the conversation we need to be having, instead of this ‘the robots are coming for your jobs’ self-fulfilling prophecy that I see every year.

…”The future is really one of human-robot interaction. …The true potential of these technologies…is for us to partner in what we’re trying to achieve.

“…But the reason that I’m so interested in (human-robot interaction) is that it’s also teaching us more about ourselves. About human communication….empathy…how we relate to others.

“(If we can integrate technology into an inclusive world that values people,) I, for one am truly excited to welcome our new robot partners and to work together to build a future that supports human flourishing.”