by Dot Cannon

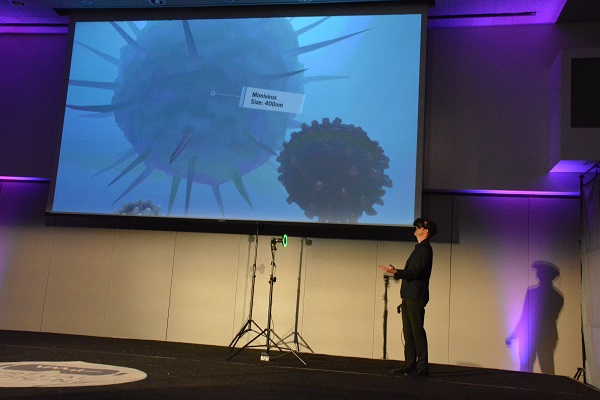

“I’m now surrounded by viruses,” said Dr. Brennan Spiegel. “I can sweep them out of the way (with my hand).”

Wednesday’s inaugural “Virtual Medicine Conference“, at Los Angeles’ Cedars-Sinai, was just getting under way. And Dr. Spiegel, who is Cedars-Sinai Health System’s Director of Health Services Research, was demonstrating the use of virtual reality in medical diagnosis.

Donning a VR headset, he had just taken the audience through several explorations inside the human body. Besides the close-up look at viruses, he demonstrated walking through a heart, inspecting a colon and looking at a uterus in action.

“That is the beginning of a baby being born. It’s happening right in front of us,” he told the audience, as a screen displayed his VR perspective.

In his opening remarks, Dr. Spiegel had outlined conference objectives to a sold-out audience of more than 300 attendees, from thirteen countries.

“We’ll be discussing, exploring and maybe even debating…the role of virtual reality in healthcare,” he explained.

Part of that role, he told the audience, was to help patients relax during hospitalization. Cedars-Sinai currently has more than 45 different VR visualizations in their library.

“I almost forgot I was here (in the hospital),” was one patient’s response, after a visualization.

In addition, a just-published study shows dramatic pain reduction among patients using VR, rather than opioids, Dr. Spiegel said. In this study, the response rate, among patients who had used VR, was 65 percent. A control group’s response rate was 45 percent.

Implementation challenges

But considerable hurdles remain before VR can be widely implemented, Dr. Spiegel added.

“How do we scale it? Who’s going to pay for it? Should we integrate it?”

In addition, he says, with virtual reality, one size does not fit all. Selecting the wrong simulation for a patient can have negative effects. One such patient was a woman with abdominal pain who started to cry after her simulation started.

“She took off the headset and said, ‘I can’t do this.’ (She came from an abusive background), and even throwing balls at bears (was something) she couldn’t handle. But they put her onstage with Cirque du Soleil, and she started to cry again–but from joy.”

While he’s currently the founder and director of Virtual Medicine, Dr. Spiegel said he had known very little about virtual reality until about three years ago. But then, vendors from medical VR firm AppliedVR gave him a demonstration. Their simulation placed him on a 50-story building–as a window washer.

“My mind was absolutely hijacked and I remember how clear it was,” he said. “I heard creaking and I started to hyperventilate.”

When the demonstrators told him to jump off the “scaffold”, Dr. Spiegel said, it was very difficult.

“They said, ‘you’re in your conference room’, but (there was a spot I could see through the headset, and) it was only because I saw carpet that I was able to throw myself off this virtual leap.”

A virtual workaround for anxiety

“Managing our attention when we are calm is relatively easy,” said Cedars-Sinai Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences Chairman Dr. Itai Danovitch during his presentation.

“But, when we are stressed…at least one of the many powers of VR is its ability to reach through the noise.”

That ability, Dr. Danovitch explained, made virtual reality effective in several areas. In addition to alleviating acute pain among burn victims, VR had proven effective in post-stroke rehabilitation. It had also proven effective in treating anxiety disorders.

“VR is so powerful because in a controlled environment, it can (expose the patient to the situation causing the fear).” he explained.

Start with VR, then add…

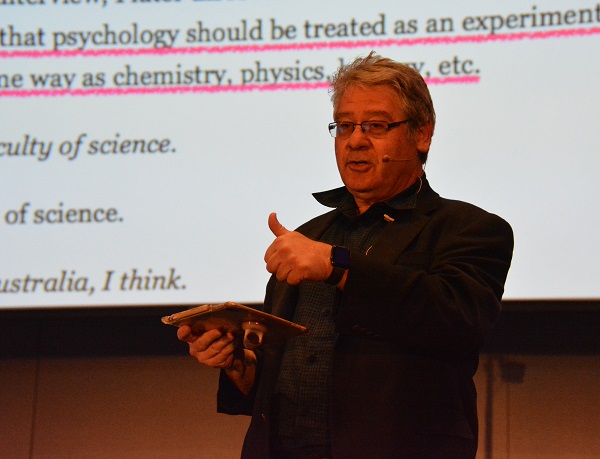

But VR needed enhancement to effectively treat anxiety disorders, said Melbourne-based clinical psychologist Dr. Les Posen, during his presentation. For effective treatment, he’d found, patients needed to experience haptics and audio.

“Distraction is OK, but it has a very limited place in anxiety work,” he said. “Two things that need to work together, are habituation and new learning.”

In his own work, treating patients’ phobia of flying, Dr. Posen said he’d simulated a flight with haptics and audio in addition to virtual-reality visualizations. The “new learning” came in with his conversation with patients, after simulating a rough takeoff.

“I say, ‘how was it?’, and they say, ‘That was awful.’ I say, ‘You are the one bringing this to the situation.'”

A sobering statistic

“By the time this conference is over (on Thursday), 90 people will have died from opioid overdoses,” said AppliedVR CEO Matthew Stoudt.

And virtual reality, he said, was needed to bridge a gap.

“Patients are being cut off from opioids by Medicaid and Medicare. Doctors have nothing else to give them (currently). We have the clinical evidence that says (virtual reality) is an effective therapeutic tool. We know it works.”

But seven steps needed to be taken before VR could take the place of the drugs, he continued. Among them were the issues of reimbursement and the fact that current technology is not necessarily intuitive.

“If we really want to make this mainstream, we’ve got to develop protocols,” he said. “The number-one complaint we get today, is (the technology is too complicated for widespread use).”

A keynoter’s vision

“How do we get truly patient-centered care?” asked Singularity University Medicine and Neuroscience Faculty Chair Dr. Daniel Kraft, during his keynote speech.

“The technology is somewhat magical, but it’s riding Moore’s Law. I want you…to imagine, with a couple more clicks of Moore’s Law, where we might be.”

A Moore’s Law scenario, where technology doubles every two years, might include a number of things, according to his presentation. Augmented reality during kitchen food preparation, as well as “virtual” cocktails with the scent and feel of a favorite beverage, were two of the innovations he envisioned. So were “smarter” avatars for well-being and healthier living.

“These mentors and coaches can come through voice,” Dr. Kraft said. “They may (use a mirror to show you) you of today, and you of tomorrow. If you stop by a bar, ‘you of tomorrow’ might say, ‘that’s not what we agreed on.'”

He also included a demonstration of new future technology–with an AR scan of Dr. Siegel’s digestive system!

“Blending all this (current) data together is going to be powerful,” Dr. Kraft continued. “You can see the patient’s data through your augmented-reality headset while interacting with the patient.”

Dolphins swimming by

The time had come for afternoon break, and attendees were eager to check out three areas of displays.

We tried The Dolphin Swim Club demo–and enjoyed seeing wild dolphins swimming around us in 360-degree panoramic views! Co-founder Marijke Sjollema and producer Benno Brada say they also have a waterproof version, complete with snorkel, that can be used in a pool.

As is the case with most great conferences, though, “Virtual Medicine” had more to see and experience than time permitted. While the first half of Day One’s program had focused on “The Present and Future of Medical VR”, the second half, themed, “VR For Pain Management”, was just about to start.

A changing field

“I think we can move the needle and transform VR from an academic curiosity into (an integral part of health care),” said Stanford University research neuroscientist and product developer Dr. Walter Greenleaf, during the first Part Two presentation.

In the past, he said, the cost of VR had prevented wide implementation–but lowered costs were driving a change. And that change, he continued, was desperately needed in the medical field.

“If we add 20 years to our current population, we’re going to be top-heavy (with senior patients outnumbering caregivers). To me, the only answer is to transform health care to technology.”

“Right now, every medical device has been (reimagined, digitally),” he said. “(With digital devices) we can understand exactly what might be going on with an individual, and what the right intervention might be for them.”

Dr. Greenleaf offered some predictions for the future.

“Room-based VR will be the way to go,” he said. “Within three years, VR will be used by 39 million users.”

Condition: critical

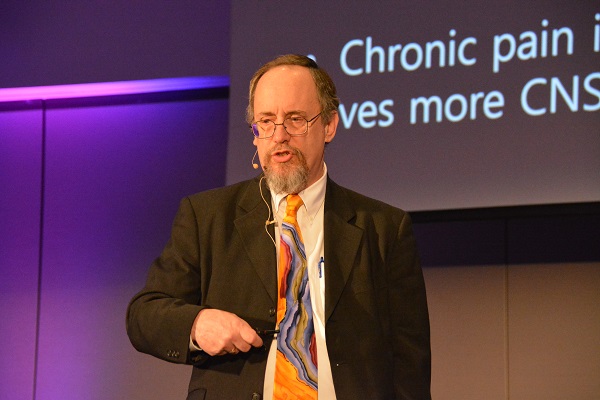

Licensed clinical psychologist and chronic-pain specialist Dr. Ted Jones highlighted a crisis in his home state of Tennessee, during his presentation.

“There is an opioid epidemic, and I’m living right in the middle of it,” he said.

“Our governor rolls out a plan: we’re suing pharmaceutical companies.”

But this action, he said, isn’t solving the problem, even as opioid use goes down. “Our overdose deaths are going up.”

While Dr. Jones said communities “needed something to fill the gap” of diminished opioid use, he asked his listeners to look at specifics.

“I’m hoping we…can move beyond, ‘VR is good for pain.’ What kind of pain, with what kind of practitioner, for what kind of treatment? What are the various models VR could use for chronic pain treatment?”

Meanwhile, UCSF Director of Health Innovation Dr. Aenor Sawyer offered some sobering statistics.

“Forty people die, every day, from overdoses of prescription narcotics,” she said. “Seventy-five percent of people dying from overdoses started from a prescription drug process.”

Contributing to the problem, she said, was the way unused medications were treated. “We don’t empower our patients to get rid of the meds they don’t use…They usually end up in the wrong hands, and over half of the people abusing opioids get them from a friend or relative.”

Virtual reality, she said, could play a role, instead, in every step of a patient’s health care.

“Starting with evaluation…to acute stay. I see at every one of those (steps) an opportunity for VR to play a role.”

Gamer and GP

“Pain, and the management of pain, is one of the main reasons patients come to see us,” said General Practitioner and VR Doctors founder Dr. Keith Grimes, who’d introduced himself as a “lifelong gamer and geek”. And, he said, deaths from opioid abuse were also rising in the U.K., where he is based.

“Mental health services are chronically underfunded, so we turn to opioids.”

But, he said, he had a different solution for his patients, very similar to the studies Cedars-Sinai has been running.

“A geek like me, what am I going to do? Turn to technology.”

Dr. Grimes told his listeners the story of his patient “Isabela”, who had been in severe pain during wound care in the 1990s. One day, when she came in for an appointment, he had his VR headset. And he had an inspiration: “If (Dr.) Shafi Ahmed can do this for people around the world, why can’t I do it for my patient?”

Accordingly, he put the headset on for Isabela. This was the first time she’d used virtual reality.

“I was so amazed taht the virtual reality (drew) me into it so much,” Isabela commented on a Skype video. “I was amazed at how it distracted me from all the pain…I would absolutely recommend it if I had to have (a dressing changed on a wound again).”

Dr. Grimes outlined three uses for virtual reality in his medical practice, including prevention of post-operative delirium. High-quality 360 immersive video, he said, was helpful in taking patients through the experience prior to surgery.

Next, he said, action–and interaction–was needed.

“We need to be moving out into the community, developing apps. But I think the most important thing is that we share some of the information we’re learning today.”

Errors, change and a challenge

For his closing keynote speech, UCSF Chairman of Medicine Dr. Robert Wachter focused on lessons learned.

“I have absolutely no background in virtual reality,” he began. “When Brennan asked me to speak, I said, ‘Are you sure?’ I’ve been here all day and I’ve learned a ton.”

But the insights Dr. Wachter shared were as pertinent to the implementation of VR as to the medical field in general.

“I’ve been thinking about patient safety for a very long time,” he commented. “Digital entered my world largely in the form of electronic health records.”

Dr. Wachter told a “horror story” which illustrated the necessity of questioning digital systems.

“The kid needed one pill, and we gave him 39. It was a glitch that could not have happened on paper…The nurse checks, and the bar code says, ‘yes, that’s right’, so she gave the kid 39 pills. He had a grand mal seizure and spent a week in ICU.”

Thankfully, Dr. Wachter said, the child survived. But the incident illustrated just how easily digitization had changed the medical profession.

“There really is no industry that, 15 years after (going) digital, had not been turned upside down,” he said. “I think plenty went wrong because we don’t understand (how complicated this is.)”

One of the things that went wrong, Dr. Wachter continued, was the barrier digitization placed between doctor and patient. To illustrate, he showed a slide of a seven-year-old girl’s drawing of her doctor visit. The child depicted her doctor sitting a distance away from her, with his back to her in the examining room.

“The only thing she got wrong, is the smile on the doctor’s face,” Dr. Wachter said, as the audience laughed.

Presenting a list of four steps for medical establishments to complete, in order to supply quality health care, he pointed out that health care professionals had so far completed only one step: digitizing the data. They had not communicated, hospital to hospital, arrived at meaningful insights from provided data or acted on those insights to improve the value of care given, he said.

But despite the ways digitization “got it wrong”, Dr. Wachter continued, he was optimistic about the future. He could see health IT entering a new phase. One major reason was the shift in the companies providing digital health care services.

“Companies in health care today are starting out as health care companies, as opposed to generic tech companies,” he explained. “The architecture of technologies is getting better. It does not require ten million hours of programming time.”

“VR has to be just another tool in the health care system,” Dr. Wachter continued. “Many uses won’t become clear until it’s in widespread use. Most of us need to have the tool out there and then the use cases emerge.

“It’s going to have to have a very important element of re-imagining the work,” he concluded. “What are we trying to accomplish, and how do we re-imagine the work in a new way?”

Thanks for the comprehensive write-up! This was truly a groundbreaking event rich with insight and thought-provoking content. It was inspiring to be part of it. – Kirstin and Steven @ Mandala Health

Thank you! Getting to cover this inaugural conference was both an honor, and, as you experienced, an inspiring look at a future that’s vastly different–with a much warmer, more patient-centered approach to healing and prevention–than predominant thinking about health care today.