by Dot Cannon

“Ultimately, this is about patients,” commented Dr. Brennan Spiegel.

“What we’re here to talk about, in the next two days, is, what is the role of VR, to improve the quality of life for our patients?”

It was Wednesday morning, March 27th, in Los Angeles. And Cedars-Sinai’s second annual “Virtual Medicine” conference was just getting under way.

The Harvey Morse Conference Center was full to capacity. 430 registrants were on hand, from 11 countries and four continents. Like 2018’s inaugural Virtual Medicine conference, the 2019 edition was sold out–but sessions were live-streaming on Cedars-Sinai’s website.

And Dr. Spiegel, who is Cedars-Sinai Health System’s Director of Health Services Research, as well as one of the two directors of the Virtual Medicine conference, started the day by sharing his own first experience with virtual reality.

A baptism by–fear

“I never heard of VR till four and a half years ago,” he said. Then, he told the audience, virtual reality medical applications expert Dr. Walter Greenleaf’s team gave him a demo.

And Dr. Spiegel found himself on a window washer’s platform, fifty floors above the street–virtually.

“I’m a little afraid of heights, but (I thought,) at least this bar is in front of me,” he explained.

“And then it fell off.”

The audience laughed as he continued. “They said, ‘jump off”. (But the simulation was so real that the only way I managed that, was that I saw a little bit of the carpet.) So I jumped off, to my first virtual death.

“And I thought, oh my God, if we can use (the way this tricks the brain) for evil, we can use it for good.”

VR and an out-of-body experience

Virtual death was something Dr. Spiegel would experience again.

Last December, he said, he and fellow Virtual Medicine director Dr. Brandon Birckhead visited Dr. Mel Slater’s Barcelona research lab. This time, VR placed him in a prone position on a table.

“They asked me to start moving my feet around on the table,” he said. “Balls started falling from the ceiling and I could kick them around and feel them. I had gained a digital doppelganger.”

Then, his perspective changed. He was out of the body, floating towards the ceiling.

“(I thought), that body is me. I have died. I’m dead…what does this mean about how my brain works?”

And the experience left him with a changed perspective on a common fear.

“In a very small way, I fear death just a little bit less.”

Prescriptions from the VR Pharmacy

Losing that fear, he continued, illustrated how VR could be used for good.

“When it’s used to recalibrate unhealthy perceptions, VR (becomes a tool to improve quality of life”.

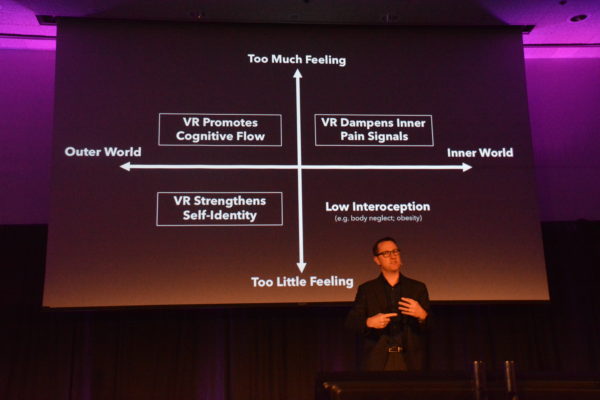

But, Dr. Spiegel added, virtual reality wasn’t “one size fits all”.

“Right patient, right time, right program,” he said. “I don’t just give everyone the same (medicine) or else I’d be a really bad doctor.”

Instead, he said, customizing virtual reality experiences to a patient’s sensitivity was key.

“These are the four quadrants of the VR pharmacy,” he explained.

“Applied VR, upper right, dampens pain. Lower left, VR restores her childhood to a woman with dementia (calming her and giving her joy).”

In addition, he continued, the upper left quadrant of the slide illustrated virtual reality improving a patient’s cognitive flow. Meanwhile, the lower right showed how VR could enhance healthy body awareness.

Dr. Spiegel told the audience that University of Tokyo scientists used virtual reality to “trick” the brain by enhancing the size of a meal. The scientists told subjects they could eat all the cookies they wanted. Then, they made the cookies look much larger through VR. Subjects that had eaten a dozen non-enhanced cookies, previously, now said they were full after eating eight!

Deflecting the arrows

Towards the end of his presentation, Dr. Spiegel also referenced Buddha’s teaching that pain involves “two arrows”.

“First, when it strikes, and second, when it’s cognitive: what does this mean to my life,” he said. But virtual reality, he added, seemed to “address both arrows”.

“(With VR we see) inattentional blindness, and time contraction. The brain doesn’t just sit here passively.

“…The brain can fight back, and say, ‘I don’t have time for pain’.”

Gamification versus chronic pain

The next speaker was Chronic Pain Research Institute and Pain Studies Lab Founding Director Dr. Diana Gromala, of Simon Fraser University. Dr. Gromala is Canada Research Chair in Computational Technologies for Transforming Pain.

And during her presentation, Dr. Gromala made a careful distinction.

Gaming, she said, was very different from chronic pain treatment in virtual reality.

“There are no biomarkers, and there’s no cure (for chronic pain),” she said. “So it’s kind of the Wild West of medicine.

“I’ve found that chronic pain patients often have some degree of sensitization. ..With gaming, stimulation can provoke anxiety.”

Dr. Gromala, who pioneered the use of immersive virtual reality for chronic pain, told the audience that at the start of her research, many of the available VR games did not serve her patients.

“We first took all the VR games we could find that were publicly available,” she said. “We came up with four games, out of 79, that chronic pain patients could tolerate.”

Her work today, she told the audience, includes a virtual reality game for aging adults, which her grad students designed. The objective: to help older patients build up, maintain and restore function.

Upon seeing the game, Dr. Gromala said, she was surprised.

“I thought, steampunk? Aging adults? Really? But the ship looks like the Yellow Submarine.”

This particular game, she said, tracks and captures the range of motion as subjects use it.

“We show them the video when we’re done, and they can’t believe they’ve moved that much.”

This is your brain, enhanced…

“How can we use technology to enhance our cognition?” asked Neuroscape Founder and Executive Director Dr. Adam Gazzaley, as he delivered the morning’s first keynote.

“We need to think about how we can create technologies that enhance us, as human beings, and do not diminish us.

Dr. Gazzaley, who is Professor in Neurology, Physiology and Psychiatry at UCSF, told the audience that UCSF had one lab and was now building 13 more, to observe the impact of digital medicine.

That research, he said, involved three areas of study: attention, perception and memory.

During his keynote, Dr. Gazzaley introduced a new device. Since his slide says it’s “proprietary and confidential”, we’ll just have to be content with telling you this: it takes users for several exciting steps, beyond what virtual reality can currently do.

But we can tell you that he also shared the concept of “the glass brain”: a VR diagnostic tool!

“You’re looking at my brain responding to playing video games,” he told the audience.

He also showed a slide of Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart playing drums in virtual reality–as an engineer measured the way his brain responded to the activity.

“We’re really intrigued by the idea of a realtime diagnostic tool. Especially one in virtual reality,” Dr. Gazzaley said.

The time had come for the morning’s first break–and to check out some of the VR demos. Day One of Virtual Medicine 2019, so far, was amazing.

And it was only about 10:30. Much more was coming.

This is Part One of a series.

Day Two of Cedars-Sinai’s second annual “Virtual Medicine” conference begins Thursday, March 28th at 9 am. While the conference is sold out, sessions will be live-streamed on Cedars-Sinai’s website.